LoRA: Low-Rank Adaptation of Large Language Models

2024-02-14

Keywords: #Quantization

0. Abstract

- Fine-tuning LLMs:

- Fine-tune the last layer: Task-specific head

- Adapter Layers: Add new intermediate modules

- Prefix Tuning: Tune prefixes for every layer

- LoRA: Rank decomposition

- Proposal: LoRA. Freezes the pretrained model weights and injects trainable rank decomposition matrices into each layer of the Transformer architecture, greatly reducing the number of trainable parameters for downstream tasks.

1. Introduction

- The major downside of fine-tuning LLMs: The new model contains as many parameters as the original model.(GPT-3 has 175 billion tranable params!)

- Adapt only some params or learn external modules for new tasks: By extending model depth, they introduce inference latency. ✪ These methods fail to match the fine-tuning baselines, posing a trade-off between efficiency and model quality.

- Inspiration: Over-parametrized models reside on a low intrinsic dimension.

- Hypothesis: The change in weights during model adaptation also has a low “intrinsic rank” → Low-Rank Adaptation (LoRA) approach.

- LoRA indirectly trains dense layers by optimizing rank decomposition matrices of the dense layers’ change during adaptation (fine-tuning), while keeping the pre-trained weights frozen. → LoRA is both storage and compute efficient.

- Contributions

- A pre-trained model can be shared. Small LoRA modules for different tasks. We can switch tasks by replacing A and B, reducing storage requirements and task-switching overhead.

- LoRA makes training more efficient. We only optimize the injected, much smaller low-rank matrices.

- The simple linear design of merging the trainable matrices with the frozen weights on deployment, introduces no inference latency.

- LoRA is orthogonal to many prior methods and can be combined with many of them.

How is it storage and compute efficient? LoRA needs the pre-trained weight AND the rank-decomposition-weights. Isn’t that more than 100% of the original model? Or does it mean that it’s efficient because we can share the original model? Meaning that we only need small LoRA modules compared to copying the original model for each task.

2. Problem Statement

- “While our proposal is agnostic to training objective”: It means that it can be applied or adapted to various training objectives without significant modification.

- Main drawback for full fine-tuning: For each downstream task, we learn a different set of params $\Delta \Phi$ whose dimensions $|\Delta \Phi|$ equals $|\Delta \Phi_0|$

- We propose to use a low-rank representation to encode $\Delta \Phi$ that is both compute and memory-efficient.

3. Aren’t Existing Solutions Good Enough?

- Adapter Layers Introduce Inference Latency

- Directly Optimizing the Prompt is Hard (prefix tuning)

4. Our Method

4.1. Low-Rank-Parametrized Update Matrices

- Weight matrices in dense layers typically have full-rank.

- When adapting to a specific task, pre-trained language models have low “intrinsic dimension” and can still learn efficiently despite a random projection to a smaller subspace.

- The updates to the weights also have a low “intrinsic rank” during adaptation.

- For a pre-trained weight matrix $W_0 \in \mathbb{R}^{d\times k}$, we constrain its update like this: $W_0 + \Delta W = W_0 + BA$ where $B \in \mathbb{R}^{d\times r}$, $A \in \mathbb{R}^{r\times k}$, $r \ll \min{(d,k)}$

- For $h=W_0x$, the modified forward pass yields: $h=W_0x + \Delta Wx= W_0x + BAx$

- Initialization: Gaussian initialization for $A$ and zero for $B$, so $\Delta W = BA$ is zero at the beginning of training.

-

Scaling: We then scale $\Delta Wx$ by $\alpha / \gamma $ (?)

- A Generalization of Full Fine-Tuning: (?)

- No Additional Inference Latency: Note that both $W_0$ and $BA$ are in $\mathbb{R}^{d\times k}$. When we need to switch to another downstream task, we can recover $W_0$ by subtracting $BA$ and then adding a different $B’A’$, a quick operation with very little memory overhead.

4.2. Applying LoRA to Transformer

- In the Transformation architecture, there are four weight matrices in the self-attention module $(W_q, W_k, W_v, W_o)$, and two in the MLP module.

- We limit the study to only adapting the attention weights and freeze the MLP modules.

- We further study the effect on adapting different types of attention weight matrices.

We leave LoRA for MLP layers, LayerNorm layer, and biases to a future work. - Has this been done?

7. Understanding the Low-Rank Updates

- Perspective #1: Low-rank structures lower the hardware barrier to run multiple experiments in parallel.

- Perspective #2: Low-rank structures give better interpretability of how the update weights are correlated with the pre-trained weights.

- A sequence of empirical studies:

- Given a param budget constraint, which subset of weight matrices in a pre-trained Transformer should we adapt to maximize performance?

- Is the "optimal" adaptation matrix $\Delta W$ really rank deficient? If so, what is a good rank to use in practice?

- What is the connection between $\Delta W$ and $W$?

7.1. Which weight matrices in Transformer should we apply LoRA to?

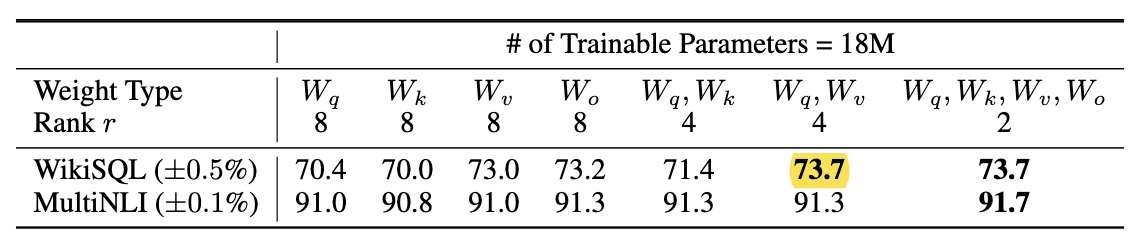

- We set a parameter budget of 18M on GPT-3 (175B), which corresponds to $r=8$ if we adapt one type of attention weights or $r=4$ if we adapt two types, for all 96 layers.

- Note that putting all the parameters in $\Delta W_q, \Delta W_v$ yields best performance.

7.2. What is the Optimal Rank $r$ for LoRA?

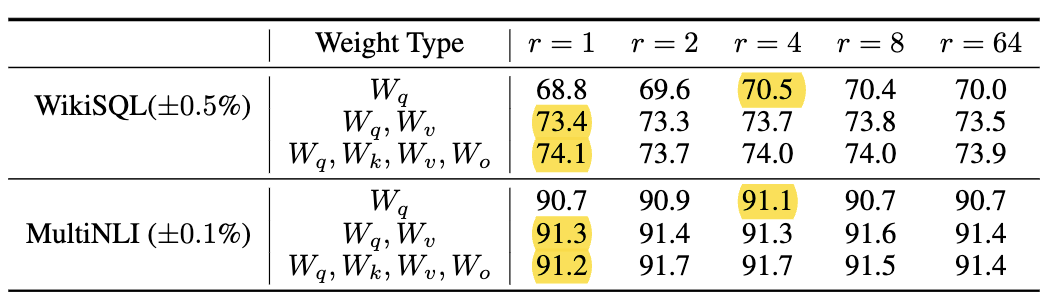

- LoRA performs competitively with $r=1$ (more so for ${W_q, W_v}$ than just $W_q$). → This suggests the update matrix $\Delta W$ have a very small “intrinsic rank”

- However, we do not expect a small $r$ to work for every task or dataset. Consider: if the downstream task were in a different language than the one used for pre-training, full fine-tuning outperforms LoRA with a small $r$. ofc

- Subspace similarity between different $r$ (?)

7.3. How does the Adaptation Matrix $\Delta W$ compare to $W$?

(?)

8. Conclusion and Future Work

- LoRA ca be combined with other efficient adaptation methods, potentially providing orthogonal improvement. ✪

- The mechanism behind fine-tuning or LoRA is far from clear – how are features learned during pre-training transformed to do well on downstream tasks? LoRA makes it more tractable to answer this than full fine-tuning.

- We mostly depend on heuristics to select the weight matrices to apply LoRA to. Are there more principled ways to do it? ✪

- Finally, the rank-deficiency of ∆W suggests that W could be rank-deficient as well, which can also be a source of inspiration for future works.